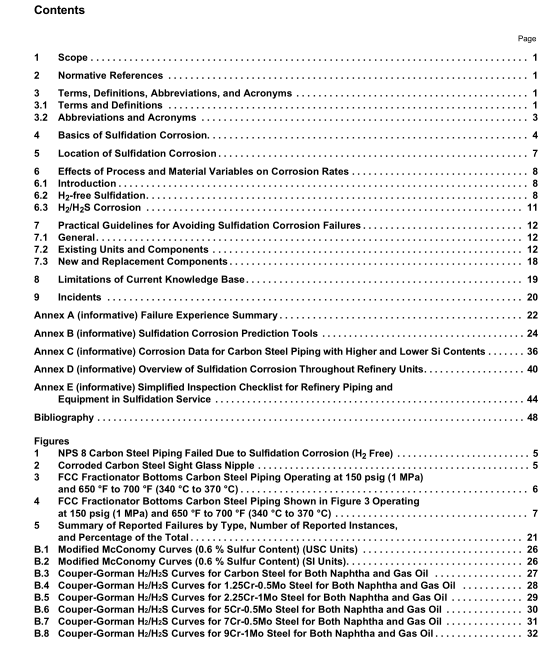

API RP 939-C pdf download

API RP 939-C pdf download Guidelines for Avoiding Sulfidation (Sulfidic) Corrosion Failures in Oil Refineries

4 Basics of Sulfidation Corrosion Sulfidation corrosion, also often referred to as “sulfidic corrosion,” is not a new phenomenon but was first observed in the late 1 800s in a pipe still (crude separation) unit, due to the naturally occurring sulfur-containing organic compounds found in crude oil. When heated for separation, the various fractions separated from the crude were found to cause corrosion of the steel equipment as a result of reaction with the sulfur-containing compounds. With the advent of FCC and coking processes, sulfidation corrosion was also experienced in these units [1 ] [2] . When hydroprocessing was introduced in the 1 950s, changes in the corrosion behavior of construction materials were noted.

This led to the recognition that a different sulfidation corrosion behavior resulted under hydroprocessing conditions that typically involve the presence of H 2 . Empirical industry data as well as laboratory research indicate that the sulfidation corrosion rate is a function of a variety of factors, including temperature, the total sulfur concentration, the types of sulfur-containing compounds present, the type of process stream (e.g. light gas or heavy oil), the velocity, heat transfer conditions, the presence or absence of H 2 , and the material of construction. In the absence of H 2 , corrosion due to sulfur-containing compounds typically is thought to occur at temperatures above 500 °F (260 °C). As discussed below, a set of curves called the “modified McConomy curves” [3] can be used to help predict corrosion rates in the absence of H 2 .

These curves show that at a given temperature and total sulfur level, steels with increasing Cr content [from carbon steel to 5Cr-0.5Mo to 9Cr-1 Mo to stainless steel (SS)] will experience lower corrosion rates. In the presence of H 2 , i.e. H 2 /H 2 S corrosion, corrosion rate starts to increase above about 450 °F (230 °C). A different set of curves, known as “the Couper-Gorman curves,” [4] can be used to help predict the corrosion rate in this environment. These curves relate the amount of H 2 S present with temperature to estimate the corrosion rate. While in H 2 -free sulfidation, 5Cr-0.5Mo and 9Cr-1 Mo have useful resistance, in H 2 /H 2 S sulfidation, there is little improvement in alloy performance until the Cr level reaches 1 2 wt %. In addition, materials such as 1 8Cr-8Ni stainless achieve a significant improvement in corrosion resistance over and above 1 2Cr wt % SS. Each crude oil or crude blend has its own characteristic chemistry, sulfur-containing organic compounds, and effect on sulfidation corrosion. Despite the industry’s best efforts, the accurate prediction of the resulting H 2 -free sulfidation corrosion rate for a specific crude oil and its fractions is an elusive technical challenge. Oil refineries that processed a consistent diet of a particular crude oil or crude blend could often base future predictions on past experience. However, over the past 20+ years, global economics have resulted in many refineries processing tens of different crudes in any given year, thus minimizing the accuracy, or even feasibility, of predictions based on historical data. Additionally, the verification of the actual sulfidation corrosion rate experienced while processing a specific crude oil is very difficult.

In both H 2 -free sulfidation and H 2 /H 2 S corrosion, the metal surface will form sulfide scales. These metal sulfide scales tend to slow down the sulfidation corrosion rate, since their formation tends to protect the underlying metal surface. In plain carbon steel, these will be iron sulfides, and in Cr-Mo steels, these will be chromium- iron sulfides. The Cr-based sulfides are more robust and protective than the plain iron sulfides, and the Cr sulfides will maintain their protection to higher temperatures and fluid velocities than iron sulfides. Sulfidation results in wastage of steel, resulting in loss of wall thickness of piping and components, heater tubes, and pressure vessels. Most industry sulfidation incidents have occurred in piping components, due to their thinner overall wall thicknesses and their higher population density vs other equipment types. Although sulfidation corrosion under certain circumstances can be isolated or localized, the majority of sulfidation corrosion damage is general or uniform in nature, i.e. present over a fairly large surface area of a given component and not dependent on differences between local conditions and bulk conditions. As a result, because the nature of the corrosion is commonly general thinning, ruptures are possible instead of a pinhole leak. Ruptures can lead to the potential release of large quantities of hydrocarbons. Figure 1 to Figure 4 depict piping components that experienced H 2 -free sulfidation corrosion.